|

Math and Aesthetics in Carpets, Faces, Art,

and Music

Asymmetry and Symmetry-Breaking

Article # 1 Symmetry Holds Key to Beauty

Abcnews.com

W A S H I N G T O N, Sept. 24,1998 — The same trait that

makes people love harmonious music may help them choose

a beautiful face,

researchers said today. This could be because humans learn

symmetrical patterns much faster than asymmetrical ones, said

Michael Ryan, a zoologist at the University of Texas and expert on the subject. "In

humans, the perceptual system is biased toward

processing

symmetrical signals," he said.

Recent studies indicate the

perception of beauty might not be subjective at all but instead

arises from a bias hard-wired into the sensory

system. Such studies have shown how

symmetrical body features, chiefly in the face, are viewed

as beautiful, while asymmetrical ones are not. Ryan said

another example is research

that suggests harmonic rather than discordant music strikes humans

as more pleasing because of the way the

inner ear works.

Senses Stimulated

Writing in the journal Science,

Ryan said a number of studies have indicated that physical traits

physically stimulate the senses. He says this

means the traditional theories about

genetic fitness do not tell the whole story about why animals and

humans choose "attractive" mates.

The genetic fitness theory holds that

pretty traits, such as the elaborate tail on a peacock, signal

that the animal is stronger and more fit in

other, invisible ways. But Ryan says

his studies show this is not necessarily true. "Mate choice

is important but it doesn’t explain all the

factors we find pleasing or beautiful," he

said.

"In a lot of cases females will

prefer more elaborate males but don’t get a reproductive

advantage."

Preprogrammed

Response

Water mites, which feed by sensing

their prey’s waterborne vibrations, are an example. Their choice

of mates is wholly unrelated to the male’s

reproductive ability, Ryan said. The

vibrations the males make mimic the vibrations made by copepods,

the prey that mites prefer.

He said the females are simply

already programmed to respond to the vibrations. "Any sensory

system is going to be more responsive to

some stimuli than to others," Ryan

said. "If males have a variety of options by which to signal

their sexual interest, females will favor those

who use signals they are already

keyed into." But he pointed out his "preferred preferences" theory

cannot by itself explain natural selection.

Rather, it is a helpful part in a

complex puzzle that includes the more traditional theories. "The

bottom line is the answer isn’t simply going to

be hypothesis A, hypothesis B

or hypothesis C," Ryan said.

Copyright (c)1998

ABCNEWS and Starwave Corporation

SYMMETRY BREAKING

article # 2

(Taken from Mathematics

and the Arts URL:

http://forum.swarthmore.edu/geometry/rugs/symmetry/

Symmetry breaking exists where symmetry is expected, but that

expectation is not met. As we often see in Oriental

carpets, it is playfulness with

symmetry that results in intriguing patterns.

In nature, symmetry is imperfect, although mathematicians may

treat it as an

ideal. ideal.

In art, too, it seems that the approximation of symmetry,

rather than its precision,

teases the mind as it pleases the

eye.

IN

CARPETS, BORDER PATTERNS

result when any or several of the basic symmetries are

repeated in one direction. The constraints of symmetry are such

that there are seven (7) possible combinations:

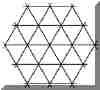

GRIDS

and

Tessellations

THE EASIEST WAY TO ANALYZE

a pattern is to locate points of rotation, and lines of symmetry.

Why? Because the rigid motions

require centers of rotation and axes

of repetition or reflection for symmetry to be present.

WHAT

IS AN AXIS? An axis is a

visible or implied line that is vertical, horizontal or diagonal, along which

designs WHAT

IS AN AXIS? An axis is a

visible or implied line that is vertical, horizontal or diagonal, along which

designs

are repeated or reflected to form patterns.

WHAT IS A GRID?

A grid is a visible or implied

series of points, or axes that intersect. Grids underlie the

structure of all two-dimensional patterns.

Grids are usually based on regular

polygons: squares, equilateral triangles, and hexagons. Or they

can be based on

rectangles, parallelograms and rhomboids.

THE ARRANGEMENT OF POLYGONS

that forms a grid is called tessellation. Other shapes may also

tessel

WHAT IS A TESSELLATION?

A tessellation is a pattern formed by the

repetition of a single unit or shape

that, when repeated, fills the plane with

no gaps and no overlaps. Familiar

examples of tessellations are the patterns

formed by paving stones or bricks,

and cross-sections of beehives.

Tessellations are not typical of

Oriental carpets except as visible grid structures.

Although they often appear in minor

borders, only rarely are tessellations used as

field patterns.

Conceptions of beauty are chiefly mathematical

Jaw length is

important to conceptions of beauty.

Childlike proportions are highly desirable

Visit

this fascinating website which shows the relationship between PHI,

the golden number, and beauty

This is a computer composite

of the most desirable features.

Synopsis of Article # 4

Emblems of Mind : The Inner Life of Music and Mathematics

Emblems of Mind : The Inner Life of Music and Mathematics

by Edward Rothstein

From Kepler and the

music of the spheres to Einstein and his violin, music and

mathematics seem to share a strong relationship. This

pathbreaking book (Emblems of

Mind) seeks to unravel the mystery at the heart of that

relationship. In this elegant exploration, music

critic Edward

Rothstein reveals the profound and

intriguing parallels between music and mathematics. Invoking the

poetry of Wordsworth,

the theories of Levi-Strauss, the images of Plato and the

philosophy of Kant, Emblems of the Mind is "a harmonious virtuoso

performance".

Math and a Music Education

In the introduction

to his recent book, Emblems of Mind, Edward Rothstein,

chief music critic for the New York Times, describes how

his

education and interests

encompassed both music and mathematics "Before setting out

to make my way in the music business," he writes,

"I was in

training to become a 'pure' mathematician. Such esoteric subjects

as algebraic topology,

measure theory, and nonstandard

analysis were my preoccupations. I

would stay up nights trying to solve knotty mathematical problems, playing

with abstract phrases

and structures. "But at the same

time, I would be lured away from these constructions by another

activity. With an enthusiasm that could

come only when critical faculties are in

happy slumber, I would listen to or play a musical composition

again and again, imprinting my ear

and mind and hands with its

logic and sense. Music and

math together satisfied a sort of abstract 'appetite,' a desire

that was partly

intellectual, partly aesthetic, partly emotional,

partly, even, physical."

Rothstein goes on to

say that such an experience is by no means unique to him. He notes

that music and math have been associated

throughout history.

Pythagoras

and his followers saw numbers as models of everything in the

physical world, and they identified music

with numbers, noting its

scales, tempos, and

other regularities. Johannes Kepler envisioned planetary

motions as the "music of the

spheres." Galileo Galilei speculated

on the numerical reasons why

some combinations of tones are more pleasing than others.

Leonhard Euler considered the same problem in a treatise

on consonance and

whole numbers. Johann Sebastian Bach sometimes

treated the

composition of canons and other types of music as exercises akin to solving

mathematical puzzles. Frederic Chopin

described the fugue

as "pure logic in music." And 20th century composers have applied

sophisticated

mathematical theory in their works.

In his 1993 book,

The Music of the Spheres, music critic Jamie James examines

and ponders the history of the concept of a musical universe --

a cosmos envisioned

as a stately, ordered mechanism both mathematical and musical.

Music and science were once intimately intertwined and

united by a grand

vision, he points out. But music, like much of the most

fundamental art and literature of our culture, has now been

relegated to the

obscure margins of

the curriculum.

"All art, including

music, was a much more serious matter before the self-conscious

aestheticism of the late nineteenth century took root,"

James argues. "It is a

recent notion that music is a divertissement to be enjoyed in

comfortable surroundings at the end of the day, far

removed from

the hurly-burly of life's

business."

I was reminded of

these ideas when I read a report in the latest issue of Nature

about a study suggesting that a weekly, structured music

program can boost reading and

math skills in early elementary school. The study was done by

Martin F. Gardiner and Alan Fox of The

Music School in Providence, R.I.,

Faith Knowles of the Kodaly Center of America, and Donna Jeffrey

of the Start with Arts Program.

The study involved 96

first graders between the ages of 5 and 7 in eight public school

classrooms. Forty-eight of the students were exposed

to a weekly singing

program that emphasized the sequenced development of pitch and

rhythm, often through musical games. The second

group of 48 attended music

appreciation classes -- musical training for that age typical of

the U.S. public school curriculum. Many of the

pupils enrolled in the singing

program had performed poorly in kindergarten, compared to those in

the second, or control, group. After

7 months of the new program, however,

children in the first group had significantly improved their

attitude and behavior, caught up in

reading ability, and

outstripped the control group in

mathematics.

The researchers found

comparable results when the study continued into the second grade,

with the addition of a few new students to the

structured singing

program. Interestingly, students who had received 2 years of extra

music showed a higher level of achievement in

mathematics than those not in the

program or those in it for only 1 year.

In their report,

Gardiner and his colleagues suggest that the pupils responded to

the "pleasurable" aspects of the weekly music program,

which motivated them to

acquire the necessary skills to progress. Such training forced

mental development that was useful in other areas of learning,

particularly

mathematics.

"The maths learning

advantage in our data could, for example, reflect the development

of mental skills such as ordering and other elements

of thinking on which

mathematical learning at this age also depends," the researchers

conclude. That's not entirely

implausible. Earlier

studies by other groups had suggested links

between improved math scores and learning to play a musical instrument.

To my mind, however,

the study reported in Nature has too many loose ends to

provide satisfactory answers to the issues it was trying to

address. There really

isn't enough information to explain how this particular musical

program appeared to succeed for this particular group

of pupils. Perhaps the

pupils simply benefited from the special attention they received

from dedicated teachers who truly loved what they

were doing and conveyed this

enthusiasm to their students. Maybe it wasn't the content of the

lessons but the spirit that mattered.

Yet the intriguing

interplay between mathematics and music, which goes back to

antiquity and possibly much earlier in human history, hints

that there may be

something deeper and more basic here.

In his conclusion,

Rothstein comments that music and mathematics share not only the

clarity of their expression but also their beauty and

mystery. "Our attempt

to comprehend music and mathematics, to understand their workings

and their purposes, is . . . a model for our

coming to know at all

-- a model for our education, for the ways we make distinctions

and connections.

"We begin with

objects that look dissimilar. We compare, find patterns, analogies

with what we already know. We step back and create

abstractions,

laws, systems, using transformations, mappings, and metaphors.

This is how mathematics grows increasingly abstract

and powerful; it is

how music obtains much of its power, with grand structures growing

out of small details."

In music and

mathematics, it may be just a modest, but mind-opening, step from

the kindergarten to the cosmos.

Copyright © 1996 by

Ivars Peterson.

ARTICLE # 5

Symmetry and ASYMMETRY in ART

Excerpt

taken from an article by

Natasha Wallace on John Singer Sargent's Lady Agnew

I remember

reading an article on the nature of beauty. It was trying to

establish

if there was some objective yardstick in which we see things as

beautiful. Their conclusions were that indeed there is an

objective establish

if there was some objective yardstick in which we see things as

beautiful. Their conclusions were that indeed there is an

objective

measure of

beauty, and it seemed to lie within the idea of symmetry. (why

symmetry?)

When I step closer to

Lady Agnew, it is apparent she is a beautiful woman with a near

perfect symmetrical face -- that is, when the face is

at rest -- "almost

schematic" is what Ratcliff calls it. But the things that I

notice, and what Ratcliff points out are the things that are

not

symmetrical and it is these things

that give her character and brings the picture to life for me --

Interesting.

Both Charteris and

Richard Ormond with Elaine Kilmurry talk in their books about the

nervous energy of the women in Sargent's portraits. Lady

Agnew is no exception

here. Although she sits with a total comfortable familiarity with

her surroundings and takes ownership of the room -- the

"languid pose", her

back to the corner of the chair, leg crossed and angled from her

left to right, there is an energy (subtle though it is)

which is palatable. Besides the mouth and

her cocked eyebrow, I notice also the hand that grips the chair,

the ever so slight downward tilt

of Lady Agnew's head (contrasted by the

hint of upward tilt to Madame X's -- although it actually doesn’t)

-- the tension here is undeniable.

The thing that

strikes me over and over about his life is that John Sargent loved

women -- women who were strong in character, intelligent

and of course beautiful

women. He didn't feel threatened by strong women (as some men

can), and above all he truly enjoyed their presence.

Yet John was not, by

anyone's measure, a wilting violet. In fact, he was a true man's

man (this comes from many sources) -- over six feet tall

and strong in physique

and sporting a full beard. His constitution was incredible and he

could push himself hard in work and he did. He

was extremely bright, well read and

seemed to retain everything he read. He was opinionated, yet

self-abasing, and his manner was charming

and humorous. He was a skilled

pianist and played often for friends and played while painting

with sitters, moving back and forth between

piano and painting. It was from music that

he seemed to draw his energy for painting and it was music that

occupied many of his sittings.

(Sargent's Musical Talents)

By: Natasha Wallace

Copyright 1998-99

Article # 6 Looking

Good: The Psychology and Biology of Beauty

Charles Feng

Human Biology, Stanford University

feng@jyi.org

In ancient

Greece, Helen of Troy, the instigator of the Trojan War, was the

paragon of beauty, exuding a physical

|

|

|

Model Cindy Crawford,

an example of symmetry

Image courtesy of

www.cindy.com |

brilliance that would put Cindy

Crawford to shame. Indeed, she was the toast of Athens, celebrated

not for her kindness or

her intellect, but for her physical perfection. But why did the

Greek men find

Helen, and other beautiful

women, so intoxicating?

In an attempt to answer this

question, the philosophers of the day devoted a great deal of time

to

this conundrum. Plato wrote of

so-called "golden proportions," in which, amongst other things,

the

width of an ideal face would be

two-thirds its length, while a nose would be no longer than the

distance between the eyes.

Plato's golden proportions, however, haven't quite held up to the

rigors

of modern psychological

and biological research -- though there is credence in the ancient

Greeks'

attempts to determine a

fundamental symmetry that humans find attractive.

Symmetry is attractive to the

human eye

Today, this symmetry has been scientifically proven to be

inherently attractive to the human eye. It has been defined

not with

proportions, but rather with similarity between the left and right

sides of the face Thus, the Greeks were only

partially

correct.

By applying the stringent

conditions of the scientific method, researchers now believe

symmetry is the answer the

Greeks were looking for.

Babies spend more time staring

at pictures of symmetric individuals than they do at photos of

asymmetric ones.

Moreover, when several faces

are averaged to create a composite -- thus covering up the

asymmetries that any

one individual may have -- a

panel of judges deemed the composite more attractive than the

individual pictures.

Victor Johnston of New Mexico

State University, for example, utilizes a program called

FacePrints, which shows

viewers facial images of

variable attractiveness. The viewers then rate the pictures on a

beauty scale from one

to nine. In what is akin to

digital Darwinism, the pictures with the best ratings are merged

together, while the l

ess attractive photos are

weeded out. Each trial ends when a viewer deems the composite a

10. All the perfect

10s are super-symmetric.

Scientists say that the

preference for symmetry is a highly evolved trait seen in many

different animals. Female

swallows, for example,

prefer males with longer and more symmetric tails, while female

zebra finches mate with

males with symmetrically

colored leg bands.

The rationale behind symmetry

preference in both humans and animals is

that symmetric individuals have

a higher mate-value; scientists believe that

this symmetry is equated

with a strong immune system. Thus, beauty is i

ndicative of more robust genes,

improving the likelihood that an individual's

offspring will survive. This

evolutionary theory is supported by research showing

that standards of

attractiveness are similar across cultures.

According to a University of

Louisville study, when shown pictures of different

individuals, Asians, Latinos,

and whites from 13 different countries all had the

same general preferences

when rating others as attractive -- that is those that

are the most symmetric.

Beauty beyond

symmetry

However, John Manning of the University of Liverpool in England

cautions against over-generalization, especially by

Western scientists. "Darwin

thought that there were few universals of physical beauty because

there was much variance

in appearance and

preference across human groups," Manning explained in email

interview. For example, Chinese men

used to prefer women with small

feet. In Shakespearean England, ankles were the rage. In some

African tribal cultures,

men like women who insert large

discs in their lips. Indeed, "we need more

cross-cultural studies to show that what is

true in Westernized

societies is also true in traditional groups," Manning said his 1999

article.

Aside from symmetry, males in

Western cultures generally prefer females with a small jaw, a

small nose, large eyes,

and defined cheekbones -

features often described as "baby faced", that resemble an

infant's. Females, however, have

a preference for males

who look more mature -- generally heart-shaped, small-chinned

faces with full lips and fair skin.

But during menstruation,

females prefer a soft-featured male to a masculine one. Indeed,

researchers found that

female perceptions of beauty

actually change throughout the month.

When viewing profiles, both

males and females prefer a face in which the forehead and jaw are

in vertical alignment.

Altogether, the preference for

youthful and even infant-like, features, especially by

menstruating women, suggest

people with these features have

more long-term potential as mates as well as an increased level of

reproductive

fitness. Scientists have also found that

the body's proportions play an important role in perceptions of

beauty

as well. In general, men have a preference for

women with low waist-to-hip ratios (WHRs), that is, more

adipose

is deposited on the hips and buttocks than on the

waist. Research shows that women with high WHRs

(whose bodies are

more tube-shaped) are more likely to suffer from

health maladies, including infertility and diabetes. However, as

is

often the case, there are exceptions to the rule.

Psychologists at Newcastle

University in England have shown that an indigenous people located

in southeast Peru,

who have had little contact

with the Western world, actually have a preference for high WHRs.

These psychologists

assert that a general

preference for low WHRs is a byproduct of Western culture.

Beauty and choosing a

mate

Psychological research suggests

that people generally choose mates with a similar level of

attractiveness. The

evolutionary theory is that by

mating with someone who has similar genes, one's own genes are

conserved. Moreover,

a person's demeanor and

personality also influences how others perceive his or her beauty.

In one study, 70% of college

students deemed an instructor physically attractive when he acted

in a friendly manner,

while only 30% found him

attractive when he was cold and distant. Indeed, when surveyed for

attributes in selecting

a mate, both males and

females felt kindness and an exciting personality were more

important in a mate than good

looks. Thus, to a certain

degree, beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder.

Douglas Yu of the University of

East Anglia in Norwich, England, agrees. "It's true by definition.

Beauty is always

judged by the receiver," he

says. At the same time, he says in an email "there is

inter-observer concordance, a measure

of objectivity," so that

individual perceptions of beauty, factoring in other

characteristics such as personality and

intelligence, can often be

aggregated to form a consensus opinion. One of the offshoots of

Yu's work in ethnobiology

was a piece in Nature

in 1998 that showed that the hourglass-body standard of beauty in

women, previously thought

to be `universally'

preferred, was in fact likely swayed by advertising.

The halo effect

In society, attractive people tend to be more intelligent, better

adjusted, and more popular. This is described as the

halo effect - due to the

perfection associated with angels. Research shows attractive

people also have more

occupational success and more

dating experience than their unattractive counterparts. One theory

behind this halo

effect is that it is accurate

-- attractive people are indeed more successful.

An alternative explanation for

attractive people achieving more in life is that we automatically

categorize others before

having an opportunity to

evaluate their personalities, based on cultural stereotypes which

say attractive people must be

intrinsically good, and ugly

people must be inherently bad. But Elliot Aronson, a social

psychologist at Stanford University,

believes self-fulfilling

prophecies - in which a person's confident self-perception,

further perpetuated by healthy feedback

from others - may play a

role in success as well. Aronson suggests, based on the

self-fulfilling prophecy that people

who feel they are attractive -

though not necessarily rated as such - are just as successful as

their counterparts who

are judged to be good-looking.

Whatever the reason, the notion

that attractiveness correlates with success still rings true. Yet

beauty is not always

advantageous, for beautiful

people, particularly attractive women, tend to be perceived as

more materialistic, snobbish,

and vain.

For

better or worse, the bottom line is that research shows beauty

matters; it pervades society and affects how we For

better or worse, the bottom line is that research shows beauty

matters; it pervades society and affects how we

choose loved ones. Thus,

striving to appear attractive may not be such a vain endeavor

after all. This isn't to say

plastic surgery is necessarily

the answer. Instead, lead a healthy lifestyle that will in turn

make you a happier person.

|